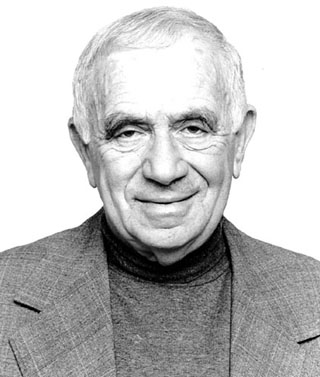

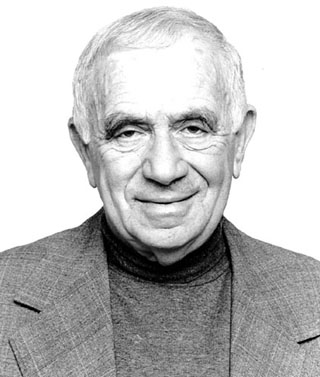

The following article appeared in Modern Hebrew Literature, No. 13, 1994,

in honor of the poet's seventieth birthday.

THE UNTRANSLATABLE AMICHAI

|

Born in Wurzburg, Germany in 1924, Yehuda Amichai moved with his family to Eretz Israel in 1935. His poetry has been translated into some 29 languages, but Amichai has also published a novel, short stories and a number of plays, and has received the prestigious Israel Prize. In honor of Amichai's birthday, The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature produced a special bibliography listing his works in translation. His German and Dutch publishers (R. Piper, Munich and Meulenhoff, Amsterdam) are publishing volumes of poetry to mark the occasion, and HarperCollins, Amichai's U.S. publisher, is preparing a landmark edition of some 500 new English translations. Below, Robert Alter considers the popularity of Amichai's poetry abroad. YEHUDA AMICHAI, it has been remarked with some justice, is the most widely translated Hebrew poet since King David. His success in English has been especially spectacular. Many volumes of his poetry are available in apt English translations and they are widely reviewed; his readings draw large crowds all over the United States; a few prominent American poets even claim to have been influenced by him. Predictably, Amichai's popularity abroad has contributed to a certain critical backlash in Israel, one particularly jaundiced recent critic going so far as to claim that this is the sort of stylistically meager poetry in which nothing is lost in translation. In fact, Amichai's continuing popularity in Israel reflects the fact that he is by no means a poet for export only, and despite the liveliness and beguiling character of his poetry in translation, there are aspects of athletic inventiveness in his Hebrew that cannot cross the translation barrier. |

There are two principal reasons why Amichai has done so well in translation. First, he is the kind of modernist who combines freshness of imagination with accessibility - more like, say, Robert Frost than like a "difficult" modernist such as T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound. Second, he is a highly successful practitioner of the plain colloquial style that was a revolution in Hebrew verse in the 1950s when he began to publish and that has close equivalents in English poetry and in other Western languages. But the colloquial character of Amichai's poetry has been somewhat exaggerated by critics and is necessarily exaggerated by his translators. If W.H. Auden was an important early influence, so was Dylan Thomas, whose poetry abounds with fractured idioms, puns, allusions, a flamboyant inventiveness of imagery, and a pervasive linguistic playfulness. Such a poetic program can be carried out only by exploiting the indigenous resources of the language in which you are working, and in Amichai's case that has involved not merely the sounds and idiomatic pattern and associations of the Hebrew words he uses but also a literary history that goes back three thousand years.

Perhaps the most subtle manifestation of the indigenously Hebrew character of Amichai's style are its frequent shifts in levels of diction. These are usually invisible in translation because the scale of diction operates rather differently in English, having more to do with social hierarchies and less to do with the historical stratification of the language. Thus, a recent poem, "Fourth Resurrection," which ponders the transience of human life in the image of a heap of old theater seats in a lot by an abandoned cinema, seems to be, at least in translation, entirely colloquial. But when the poet asks, "Where are the feats and where are the words that were on the screen," he chooses of the three Hebrew words for "where" not the ordinary eifo and not the modern middle-diction heikhan (which he uses a little further on in the poem) but the archaic ei. Any Hebrew reader will recognize that this term belongs to the poetic layer of biblical language and so will immediately sense a heightening of style. The informed reader will identify this, along with a couple of other clues, as an allusive marker to a famous ubi sunt - "Where are they now?" - poem ("I Billeted a Strong Force") by the great medieval poet Shmuel Hanagid, whom Amichai has long admired. As one might assume, Amichai's exploitation of indigenous stylistic resources is often connected with his sensitivity to the expressive sounds of the Hebrew words he uses and with his inventive puns, which are sometimes playful, sometimes dead serious, and often both at once. But what is most untranslatable are the extraordinary allusive twists he gives to densely specific Hebrew terms and texts. In a love poem ("In the Middle of This Century") he speaks of "the linsey-woolsey of our being together." This literal rendering sounds silly, but the Hebrew reader will identify in the term sha'atnez the biblically prohibited interweave of linen and wool and grasp it as a beautifully succinct image of an an impossible union of disparate elements, and one that may be taboo. When at the end of "At a Right Angle," Amichai writes that "God is seething the kid in its mother's pain," an English reader may readily see the allusion to a more famous biblical prohibition ("You shall not seethe a kid in its mother's milk") but the intertextual electricity is more incandescent in the Hebrew because "pain," ke'ev and "milk of," khaleiv, are so similar in sound. Other inventions absolutely resist translation.

In "Farewell," one of Amichai's most innovative poems, the sadly parting lover says, "That everything was though our word, that everything of sand." But the Hebrew for "that everything," shehakol, is the name of a blessing recited before drinking beverages - one blesses the all-providing God, "that everything was through His word." The word for "sand", then khol, must also reflect its homonym, "profane," and the complications of meaning in these half-dozen Hebrew words become dizzying. In stressing the distinctively Hebrew Amichai, I have tried to shed light on the other half of the often stated half-truth about his accessible colloquial style. Despite Robert Frost's frequently cited statement that poetry is what gets lost in translation, there is a great deal, certainly in Amichai, that is vividly retained in translation, and readers across the world are right to be grateful for all that can be happily conveyed in their own languages. But it is salutary to remember that Amichai is not simply an Auden or a William Carlos Williams writing from right to left, that he uses his own language and literary tradition as a delicately tuned instrument that communicates to Hebrew readers certain tonalities that others will not hear.